Three Sisters from Gordon Falls Lookout (Ian Brown)

Three Sisters from Gordon Falls Lookout (Ian Brown)

An inspiring aspect of the Blue Mountains is the atmospherics of changeable weather, here engulfing our most famous landmark.

The Three Sisters were declared an Aboriginal Place in 2014 to recognise and protect the feature and surrounds as a site of mythological and other cultural importance.

We now know that the valley was carved by the Grose River, wearing slowly away at the layered rocks over millions of years.

Blue Mountains National Park (Courtesy NPWS)

Blue Mountains National Park (Courtesy NPWS)

The "national spectacle" of the Grose Valley was protected from development as early as 1875, and later became the scene of one of the first public environmental campaigns in Australian history.

Bushwalkers and others banded together to save the magnificent Blue Gum Forest from the axe in 1932. They paid the leaseholder to relinquish his rights over the river flat at the junction of the Grose River and Govetts Creek, and then convinced the NSW government to make the area a reserve.

So it was no coincidence that in 1959 the Grose Valley became the core of the first national park to be declared in the Greater Blue Mountains.

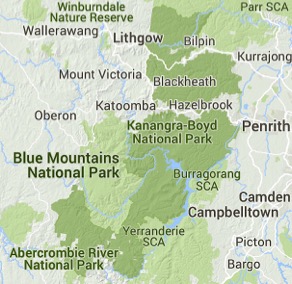

Blue Mountains National Park was progressively expanded over the next 50 years to take in over 267,000 hectares in 2010. It was the kernel around which more parks grew, until one million hectares of protected land was recognised as the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area in the year 2000.

Most people know Blue Mountains National Park as that vast sweep of ochre cliffs and blue valleys that spread north and south from the City of Blue Mountains – the chain of villages along the ridgeline followed by the Great Western Highway.

Since Charles Darwin visited what is now Govetts Leap and Wentworth Falls, the park has been viewed by millions of other tourists from the many popular cliff-top lookouts. A web of walking tracks, some of them over 100 years old, wind through the escarpments, waterfalls, grottoes, glens and forests from centres such as Katoomba, Blackheath and Springwood, where cafes and art galleries add to the variety of enjoyments. But Blue Mountains National Park is much more than this.

It reaches over the horizon to north and south, and away in the east to the plains of western Sydney. Southwards, the park takes in much of the pristine western catchment of Lake Burragorang, the water supply for six million people.

It almost completely surrounds Kanangra-Boyd National Park and protects some of the diverse geology that underlies the sediments of the Sydney Basin.

Northwards, beyond the Grose Valley and Bells Line of Road, the park includes the intricate canyon country of the Wollangambe Wilderness, and joins Wollemi National Park. To the east, the Hawkesbury Sandstone landscape of the lower Grose Valley and the well-named Blue Labyrinth is more subdued but full of different species.

Blue Gum Forest is the most famous stand of these regal trees that are widespread in the lower altitudes of the Greater Blue Mountains.

In the 1930s the forest was threatened with clear-felling, until bought by a coalition of bushwalkers and other nature lovers and donated back to the people as a reserve - and an early addition to the growth of Blue Mountains National Park.

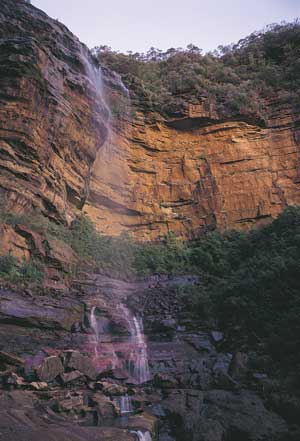

The waterfalls, forests, walking track networks and lookouts of the Jamison Valley escarpment make it the epicentre of tourism in the Blue Mountains.

Wentworth Falls also happens to be the epicentre for the rare Dwarf Mountain Pine (Pherosphaera fitzgeraldii), a Gondwanan survivor that lives on just 10 wet cliff sites.

The cliff-walled Jamison Valley is bounded on the north by the townships of Katoomba, Leura and Wentworth Falls with their networks of historic walking tracks, lookouts, waterfalls and coffee shops.

Narrow Neck, Mount Solitary and Kings Tableland enclose the other sides, with the Kedumba River flowing out from the south-east corner to Lake Burragorang (Sydney's main water supply).

The Blue Labyrinth was named by early bushwalkers who explored the maze of ridges and gorges, before topographic maps existed and fire trails carved up the area.

Part of the Blue Labyrinth was included in the creation of the embryonic Blue Mountains National Park in 1959, and the rest progressively added from 1967. Much of the area remains a relatively untrodden 'de facto' wilderness of clean waters and rich Aboriginal heritage.

The historic National Pass (1908) links a chain of waterfalls in The Valley of the Waters to Wentworth Falls itself, along a spectacular 'halfway' ledge.

After an extensive renovation by the National Parks and Wildlife Service the track is one of the most renowned and popular half-day walks in the Blue Mountains … and rightly so!